City and Canada Bay – Thursday Morning 14th November 2024.

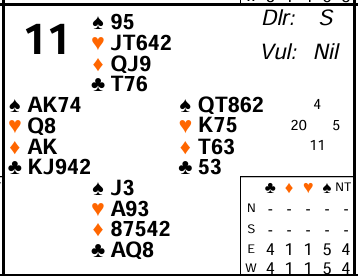

Board 11 last week had almost all East West pairs playing in 4♠. That’s the normal contract but how they got there may well have varied. The hand shows how important it is to distinguish in the auction between when partner has been forced to bid and when he hasn’t. There was also some interest in the play to make the maximum number of available tricks.

South has the first decision about whether to open or not. These days I suspect many will have done – it’s a balanced 11 point hand but it does contain two aces and there are many advantages to getting into the auction first. So I’d certainly be tempted to open 1♦ (or 1NT if playing a weak NT).

But let’s first briefly consider what would happen if South didn’t open. West would then most likely open 1♣ (although 2NT is also possible – see advanced section). After 1♣ East would respond 1♠ and West would raise straight to 4♠. After 2NT East would transfer to spades and then bid 3NT which West would convert to 4♠.

Now suppose South does open. This time West will have to start with a double – nothing else is possible. Yes initially East will assume that’s a normal takeout double of 1♦, but West will clarify his actual hand type on the next round (usually by rebidding NT).

Might North respond 1♥ after 1♦ X? Most probably wouldn’t with only 4 points although there is some temptation with a 5 card major and QJx in partner’s opened suit. Whether or not North does bid, East will surely next bid 1♠. But this is where an important distinction arises. There is a world of difference between these two auctions:

1♦ (X) P 1♠ and 1♦ (X) 1♥ 1♠.

Why? Because in the first East is basically forced to bid. After North passes he can’t leave 1♦ X in as a contract so he might have to bid 1♠ on a 4333 zero point hand. But in the second auction that’s not the case. Once North bids 1♥, East has the option to pass and that’s obviously what he would do with a 4333 zero point hand! So in THIS auction when he bids 1♠ he has voluntarily chosen to do so when he didn’t have to – this is sometimes referred to as a “free bid”. When he does this he is showing some values. Here he has 5 points and a 5 card suit so, while it’s obviously not great, it’s not a pile of rubbish and is definitely worth showing over what he thinks is a takeout double of 1♦.

That should make a difference to West’s rebid. In the 2nd auction when partner actively shows something he will clearly just raise to 4♠ (that’s basically the same as the uncontested auction 1♣ P 1♠ where again partner could have passed with nothing but has instead consciously responded 1♠ so at least has 5/6+ points). But in the 1st auction West should only rebid 3♠ because he needs to allow for the fact that partner might have nothing. Now it’s back to East and he should also appreciate that his 1♠ bid COULD have been based on nothing but he actually has a fair bit more than that. Hence he should raise 3♠ to 4♠. So the same ultimate contract is reached but by different routes.

See advanced section for some other knock-on effects when responding to takeout doubles and also what West would rebid if East hadn’t conveniently bid a suit that he has 4 card support for.

So what about the play? Most Souths led a diamond against 4♠ so it was over to declarer. Making the contract isn’t hard – there are 5 trumps, 1 heart, 2 diamonds and 2 red suit ruffs in the West hand. That’s 10 tricks before considering the club suit. But when playing matchpoint pairs you want to make every overtrick you can so you should be aiming for 11 tricks losing just 1 club and the ♥A. The key is to be able to lead towards the ♣KJxxx in dummy. You don’t want to have to lead away from it as the defence will then be guaranteed two club tricks. That means entries to the East hand are critical. After winning the diamond lead, many declarers may have cashed ♠AK. What it isn’t then safe to do is cross to hand with a 3rd round of trumps (because you want 2 trumps left in the West hand to be able to ruff the two red suit losers). So the next play is likely to be ♥Q to knock out the ♥A. That might work – declarer then wins ♥K in hand and can lead a club up at that stage. But that isn’t the right line of play (see advanced section for why) – declarer should instead play ♠A and then cross to ♠Q in hand. Today because trumps are 2-2 that draws all the trumps and he can then lead a club up. At the time he does that he may think it’s a guess but on the hand he can’t go wrong since South has both ♣AQ. That secures a club trick in addition to the 10 tricks referred to above.

Key points to note

After you make a takeout double your partner might be forced to respond on nothing – you need to take this into account with your rebid. It is not the same as partner voluntarily responding to an opening bid or voluntarily bidding in a contested auction when he had pass available.

When responding to a takeout double you should jump with about 8-11 points (so partner can distinguish when you do have some values and be able to move on with a better than minimum hand of around 16 points).

In pairs play you want to make the most tricks possible. So when planning the play consider entries carefully to be able to lead up to honours in suits rather than have to lead away from them. But remember that good defenders may also duck to deny you these entries!

More advanced

I said West might choose to open 2NT (usually showing 20-22). It’s slightly off-shape for that being 4225 but it’s not unreasonable – it gets the strength of the hand across and won’t usually miss a spade fit because East will be able to use stayman, transfers, etc. The downside might be the 5th club isn’t ever shown and a possible 6♣ contract might be missed. Here, because the shape is specifically 4225, it’s unlikely to be a problem to open 1♣. West will be able to rebid his spade suit quite easily. If he were 2425 then NT perhaps becomes preferred because after, say, 1♣ P 1♠ he would reverse with 2♥ and partner may think he has a more shapely hand than he really does. How to treat this hand is very much a question of personal and partnership style.

After South does open 1♦ and West doubles what will his plan usually be? Here it’s easy because partner bids spades but what if partner responds 1♥? Now West should rebid 1NT. Bearing in mind that an immediate 1NT overcall would have been 15-18 (this is the most common range although it does vary a bit), the fact that he has doubled first and THEN rebid NT shows he has a hand too strong to do this – i.e. 19-20 balanced (had East responded 2♣ then he would rebid 2NT showing the same).

There’s another implication when East responds to West’s takeout double and North has passed. We said earlier that 1♠ might then have to be bid on a complete pile of rubbish. Here West has such a good hand that he will have another go anyway but what if West wasn’t quite so good – say around 16 points? If partner does have rubbish he doesn’t want to bid any more but if partner has more then game may still be possible. West can’t of course know that. So it’s East that needs to help. With more values himself he needs to do something more than just 1♠ in his response. So a minimum 1♠ response is typically about 0 to a bad 8. With a good 8-11 he should jump to 2♠. Now West can pass with a min takeout double but can bid on with more. Note how a 1♥ bid from North changes things a bit. As we saw above this time East can pass with rubbish so when he makes a free bid of 1♠ he is already showing something (usually about 5-8 and a jump to 2♠ would be about 9-11). If East had even more than that he can make a cue bid of the opponent’s suit to force the bidding.

Responding to takeout doubles is an area where many players go wrong. Time and again you see players responding 1♠ with say 12 points (the same that they would over an opening BID from partner), then the takeout doubler raising with, say 13 points (again what they would do after a 1♠ response in an uncontested auction) and now responder catches up. Both partners are blissfully unaware they have misbid! In fact the takeout doubler with 13 points shouldn’t move again because partner might have had to bid on zero points. Hence the responder with 12 points should have been bidding a lot more than 1♠ to start with.

I mentioned that in the play of 4♠ it’s not right to cash ♠AK and then play ♥Q. Why not? Because South could duck ♥Q and wait to win the next round. Then he can exit another heart or a diamond to force the lead back into the West hand. Declarer still hasn’t got his entry to hand to lead a club up. South should find this defence too because he’s looking at ♣AQ and knows full well he doesn’t want a club led through him! In fact declarer could still make 11 tricks but to do so he has to put 4♠ at risk by wasting a 3rd (unnecessary) round of trumps to reach hand and only survives because the club layout is so favourable. 3-3 with both honours onside means that whatever South does, declarer will be able to set the club suit up by ruffing one in hand. While this sort of club position is often going to be a guess, declarer may have a clue from the bidding here. If South has opened 1♦ then he is far more likely to hold ♣A so declarer can play the ♣K with a fair degree of confidence.

In practice, if declarer reaches that point he is not likely to risk the 4♠ contract and will just concede 2 club tricks which is no doubt why quite a number of declarers scored 420 instead of 450. As usual in matchpoint pairs those who did score the extra trick to make 450 were rewarded with a joint top.

Julian Foster (many times NSW representative) ♣♦♥♠